Ten (!) years ago today, Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-Creator of Batman came out. Hard as it still may be to believe, it was the first book about Bill Finger—38 years after he died.

If you’d told me then that this unassuming picture (!) book would be followed by a historic credit change, an unprecedented Hulu documentary, a New York City street renaming, and more than one style of Bill Finger T-shirt, I’d have asked if I could feel your forehead.

The first was in Spanish, the second in Portuguese, and the new one in French. (Then there’s the Polish edition of my book.) I speak none of these languages, though I took French in school for five years. (In my defense, those five years weren’t last week.)

This latest Bill Finger book is the second illustrated biography. Yes, we’ve gotten to the point where there is more than one of certain formats.

Though Julian is not French, the first publisher to make an offer on his manuscript was. He is hoping to also put out an edition in English.

Julian was kind enough to involve me in the editing process of the book, and I greatly appreciated that because I am not only protective of Bill’s legacy but also a central figure in his telling. He sent his first draft and Erez’s initial sketches for my review in 2019.

It was and still is surreal to see my 2006-07 research experiences recreated so vividly. I imagine people who are depicted by someone else (in words, art, or both) often feel it’s a mix of humbling and strange. Those research moments were so private, so localized, so inward. No one (besides me) was documenting me then. I didn’t even have a book contract yet. I had no idea if any of that work would amount to anything.

confirming the apartment where a

(example of creative license;

at no point in the research did I do a cartwheel)

finding a previously unpublished

(again an instance of creative license;

we did not rendezvous on a street corner)

Both Julian and Erez were highly receptive to my feedback (which, true to form, was detailed). An example: Julian uses a storytelling device in which the adult me interacts with the kid me (specifically me dressed in a Robin-inspired costume).

Side note: whether intentional or not, this is reminiscent of Robin’s original purpose in Batman comics—to give a loner main character someone to talk to, and therefore help convey information to the reader without having to use monologue or voiceover.

The original drawings of my Robin costume had a “N” (for Nobleman) instead of Robin’s “R.” I understood that Julian and Erez were taking creative license, and I accepted it in other instances, but in this case I asked if they would either stick with “R” or do away with a letter altogether. Life as we know it would hardly screech to a halt if this little fabrication remained intact, but it felt a bit too self-aware for my taste, and the dynamic duo graciously obliged.

The book is 136 pages with a trim size roughly that of a standard magazine. It is gorgeous and heartfelt. I’m honored that I had a small role in it.

Here is the introduction I wrote for the book:

Oh, you’re partial to English? Thy shall be done:

His Identity Remains Known

Truly by chance, I began to write this on September 18, 2021—which is, as I’m sure you immediately realized, the sixth anniversary of the announcement that DC Entertainment would add Bill Finger’s name to the Batman “created by” line…76 years late.

I don’t need an anniversary to celebrate Bill Finger. I’ve been doing it almost daily since I began researching him in 2006, though those early months were mostly a party of one.

Bill was, creatively, the primary influence behind a character who became one of the most iconic fictional heroes of all time. Ask a person who has never read a Batman story or seen a Batman show/film to name three things related to the Dark Knight. First, she will be able to do that. Second, unless she says “Harley Quinn,” all three will almost certainly be Bill contributions.

I set out to write a book, but I knew from the start that I was also setting out to try to fix a mistake. It’s still mystifying to me that no one had already published a biography of Bill, and I remain grateful that, somehow, I got to be the first.

That’s not to say that no one knew of Bill. Thanks to fandom chatter at comic conventions and later message boards and social media, word spread that artist Bob Kane was not alone at bat. Some lamented Bill’s fate and called for justice. But because Bill wrongly appeared as only a cameo in most published sources covering the Batman creation story, many fans knew little about the degree of his involvement…and almost nothing about the man himself.

That began to change in 1965, on the eve of the debut of the now-mythic TV show that elevated Batman from comic book hero to pop culture icon.

Batmanians (a pre-existing word, yo) owe a cave-sized debt to a man named Jerry Bails.

Jerry was many things to comics history, notably the first known person to interview Bill Finger. Based on what Jerry learned from that interview, he wrote a two-page article. It was not published in Time or Newsweek, though some form of it could’ve and should’ve been. Instead, Jerry mimeographed it (blue paper, smudgy purple ink) and mailed those copies to other Batman fans—Batmanians—nationwide. Simple as this seems, it was a radical move. Jerry was a fan first. But not at the expense of the truth. And this truth was titanic. It would debunk (and therefore irk) one of the most famous names in the business.

I had the privilege of corresponding with Jerry about Bill. I received his first email on May 31, 2006, and last on August 14. I’d reached him just in time; only three months later, Jerry died. He might’ve thought that I was just another annoying wannabe crusader who would never follow through on a book. I wish he knew that he passed the Bill baton to someone who was willing to stick to the mission. Perhaps I should say Bat-on… (It’s okay. Bill used puns.)

Other Bill champions who predated me and whom I acknowledge whenever possible include superfan Tom Fagan, Bill’s longtime writing partner Charles Sinclair, comics legend Jim Steranko, comics writer Mike W. Barr, Bob Kane biographer Tom Andrae, Bill’s second wife Lyn Simmons, and early Batman ghost artist/creator advocate Jerry Robinson. In various ways, each of them did something meaningful on behalf of Bill’s legacy, sometimes after his untimely death at age 59. Unfortunately, like Bails, Fagan and Robinson also died too soon (2008 and 2011, respectively) to see Bill get his long overdue validation.

In my efforts to commemorate Bill, I failed…a lot:

- Bill the Boy Wonder was rejected 34 times (including three times by the editor of my previous superhero-related biography, Boys of Steel: The Creators of Superman).

- Batman & Bill was the third attempt to make a documentary about Bill Finger; the first two attempts imploded, in 2009 and 2011 (though footage from each is in the final film).

- I proposed the installation of a statue or memorial for Bill in New York City (where Batman was born). I was dismissively told that Bill is not a suitable subject.

- I proposed a Google Doodle for what would have been Bill’s 100th birthday (as well as Batman’s 75th anniversary and the 40th anniversary of Bill’s death). Even though the public flooded Google with support for the idea—I think the biggest push for a Doodle up till that point—it wasn’t enough.

Even in death, Bill couldn’t catch a break.

Why go through all of this for a person who had been dead for two generations? Especially a person who, by virtue of being a white man, had privilege, not to mention steady writing work for 25 years and, some argue, obligation to speak up more forcefully for himself?

Because no matter what, you should get credit for what you do (good and bad). Credit is a key component of our dignity. Lack of credit for one of us is an existential threat to all of us. This fight was for Bill, of course, but also for every creative whose intellectual property has been stolen. Taking a person’s idea is saying “You have something of value but you yourself are not valuable enough to be acknowledged.”

Family, friends, and fans tried for decades to get recognition for Bill. Some, like me, were told flat-out: I’m all for it but don’t waste your time. It will never happen.

It took far too long, but it did happen. If Bill’s legacy was preserved despite the odds, anyone’s can be—with persistence. No story starts with “Let me tell you about the time I gave up…”

A credit is like a gravestone—a forever marker to honor a person. Both are surrounded by beauty (gravestone by nature, credit by art). Bill Finger has no gravestone, but now, finally, he has credit. Official credit. On every Batman story. Way better than a statue.

The last line of the first panel of the first Batman (then “Bat-Man”) story is “His identity remains unknown.” Bill wrote it referring, of course, to Bruce Wayne’s secret identity—but eerily, unknowingly, it would also come to describe Bill himself. Yet like the hyphen in the hero’s name, Bill’s anonymous status is now a thing of the past. Now his identity remains known, permanently. I only hope that he knows it.

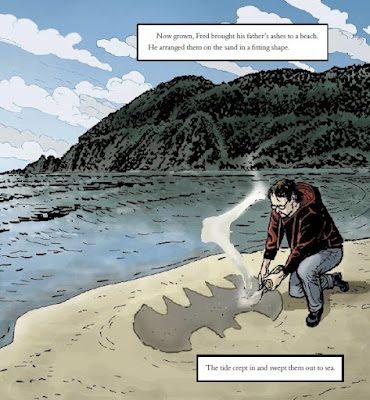

Fred Finger on an Oregon beach,

3/27/24 addendum: now available in German.

%20-%20cropped%20and%20color-corrected.jpg)

%20-%20ashes.jpg)